This post carries on from Mary Queen of Scots – Part One, a two-part article commemorating the anniversary of the execution of Mary Queen of Scots.

On the 29th October, Parliament met to discuss the fate of Mary Queen of Scots. Alison Weir writes of how Parliament “unanimously ratified the commissioners’ verdict” and demanded the execution of Mary. On the 12th November, a delegation of 40 MPs and 20 peers presented Elizabeth with a petition demanding that “a just sentence might be followed by as just an execution”.

Elizabeth, who had distanced herself from Parliament, was still indecisive and still could not bring herself to act against “her own sex and kin”, saying “I tell you that in this late Act of Parliament you have laid a hard hand on me, that I must give directions for her death, which cannot be but a most grievous and irksome burden to me.” Instead of giving Parliament the answer they wanted, she stalled again, saying that she would pray about the matter. On 24th November, Parliament again requested that Elizabeth sanction the execution but again she stalled, writing in reply:-

“Since it is now resolved that my surety cannot be established without a princess’s head, full grievous is the way that I, who have in my time pardoned so many rebels and winked at so many treasons, should now be forced to this proceeding against such a person. What, will my enemies not say, that for the safety of her life a maiden queen could be content to spill the blood even of her own kinswoman? I may therefore well complain that any man should think me given to cruelty, whereof I am so guiltless and innocent. Nay, I am so far from it that for mine own life I would not touch her. If other means might be found out, [I would take more pleasure] than in any other thing under the sun.”

and then concluded with what Alison Weir quite rightly describes as “a typically obscure statement”:-

“If I should say unto you that I mean not to grant your petition, by my faith I should say unto you more than perhaps I mean. And if I should say unto you I mean to grant your petition, I should then tell you more than is fit for you to know. I am not so void of judgement as not to see mine own peril, nor so careless as not to weigh that my life daily is in hazard. But since so many have both written and spoken against me, I pray you to accept my thankfulness, to excuse my doubtfulness, and to take in good part my answer answerless.”

What??? Can’t you just picture William Cecil banging his head against a brick wall? I can! On that same day, Elizabeth drafted a formal proclamation of Mary’s sentence but before it could be published Elizabeth sent a message stopping it and adjourning Parliament for a week. After the commissioners met again in the Star Chamber and formally condemned Mary to death, Parliament met on the 2nd December where a draft proclamation of sentence, written by Elizabeth and Burghley, was published. Walsingham drafted a warrant for the execution but it seemed that any celebrating was premature as Elizabeth was reluctant to sign the warrant.

Weir describes Elizabeth’s dilemma:-

“If she signed the warrant she would be setting a precedent for condemning an anointed queen to death, and would also be spilling the blood of her kinswoman. To do this would court the opprobroum of the whole world, and might provoke the Catholic powers to vengeful retribution. Yet, if she showed mercy, Mary would remain the focus of Catholic plotting for the rest of her life, to the great peril of Elizabeth and her kingdom. Elizabeth knew where her duty lay, but she did no want to be responsible for Mary’s death.”

She was caught between a rock and a hard place!

The Davison Debacle

After months of stress, near breakdown and using delay tactic after delay tactic, Elizabeth finally took action on the 1st February 1587, calling for Sir William Davison. According to Davison, Elizabeth read Mary’s death warrant, signed it and told him that she wished the execution to take place in the Great Hall of Fotheringhay Castle without delay, for she was disturbed by reports of an attempt to rescue Mary. As instructed, Davison asked Sir Christopher Hatton, the acting Lord Chancellor, to seal the warrant with the Great Seal of England to validate it. The next day, the Queen called for Davison and asked him not to take the warrant to Hatton. When Davison explained that it was too late, that the warrant had been sealed, Elizabeth seemed to panic and asked him why he had been in such a hurry. A worried Davison went straight to Hatton and then the two men hurried to Lord Burghley, fearing that Elizabeth was about to change her mind. According to Weir, Burghley was resolute and decided that no councillor should discuss the matter with Elizabeth until Mary had been executed. He then drafted an order for the sentence to be carried out and all ten councillors agreed to share the responsibility for it, in case Davison was blamed. The order was then copied and sent to Fotheringhay on the 4th February along with the warrant signed by Elizabeth.

Elizabeth’ story of the warrant differs from Davison’s. She claimed that she had signed the warrant and then asked Davison not to disclose this fact to anyone. When she learned that it had been sealed with the Great Seal, she then asked Davison to swear on his life that he would not let the warrant out of his hands unless he had permission from her.

Had Davison misunderstood the Queen’s instructions and intentions? Probably not. Some historians believe that Burghley chose Davison to be a scapegoat because he realised that Elizabeth needed someone to take the responsibility for Mary’s death away from her, but others believe that it was Elizabeth who chose Davison as the scapegoat. Weir believes the second theory because she points out that Burghley would not have seen Davison, a man whom he respected and liked and who was good at his job, as being expendable.

Weir also gives further details of the Davison episode. Apparently, after signing the warrant, Elizabeth had asked Davison to ask Paulet if he could get rid of Mary and ease her of her burden, so that she could announce Mary’s death by natural causes and not be forced into executing her. Davison was shocked by this idea but agreed to ask Paulet who replied by saying that he would not commit murder and that Mary should be executed lawfully. It is interesting that Elizabeth found it so hard to sign the warrant but would happily (well, ok, not happily!) order the Scots Queen’s murder!

While Elizabeth was worrying about Paulet, Mary’s death warrant arrived at Fotheringhay and Paulet told Mary that her execution was set for he next day, the 8th February, at 8 o’clock in the morning. Mary spent her evening writing farewell letters, giving instructions regarding the disposal of her belongings and praying.

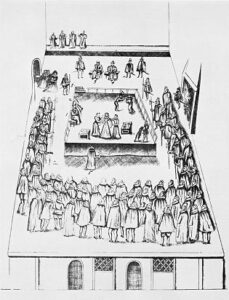

At 8 o’clock on the morning of the 8th February 1587, Mary Queen of Scots was taken to the Great Hall of Fotheringhay Castle. She was escorted by her ladies, her apothecary, her surgeon, the master of her household and the Sheriff of Northampton. Three hundred spectators filled the hall and watched as the dignified Mary Stuart entered the room and approached the scaffold which was covered with straw and draped with black cloth. Here is a description of the Scots Queen:-

“On her head a dressing of lawn edged with bone lace; a pomander chain and an Agnus Dei; about her neck a crucifix of gold; and in her hand a crucifix of bone with a wooden cross, and a pair of beads at her girdle, with a medal in the end of them; a veil of lawn fasyened to her caul, bowed out with wire, and edged round about with bone lace. A gown of black satin, printed, with long sleeves to the ground, set with buttons of jet and trimmed with pearl, and short sleeves of satin, cut with a pair of sleeves of purple velvet.”

On approaching the scaffold, Mary turned to her ladies and said: “Thou hast cause rather to joy than to mourn, for now shalt thou see Mary Stuart’s troubles receive their long-expected end.”

As the Dean of Peterborough prayed aloud, Mary read her Catholic Latin prayers in a louder voice, attempting to block out his protestant prayers. Then, refusing the help of the executioner and his assistant, saying “I was not wont to have my clothes plucked off by such grooms, nor did I ever put off my clothes before such a company”, Mary took off her black gown to reveal a bodice and petticoat of scarlet, the colour of martyrs. By wearing red, she was proclaiming that she was to die as a Catholic martyr.

The executioner then knelt and begged her forgiveness for what he had to do and Mary replied bravely “I hope you shall make an end of all my troubles.” She then knelt, laid her head on the block before her and repeated “In manuas tuas, Domine, confide spiritum meum” meaning “Into Thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit”. Alison Weir writes that it took two blows of the axe to sever Mary’s head and that it was reported that her lips carried on moving for 15 minutes afterwards. Lady Antonia Fraser also writes that it took two blows to kill Mary. Weir continues to describe how the executioner then picked up Mary’s head by the hair, as was custom, but that her lawn cap fell off along with a red wig, revealing that Mary’s real hair was grey and “polled very short”. Weir also retells the story of Mary’s dog, saying that when the executioner went to remove Mary’s clothes, as had been ordered:-

“he found her little dog under her coat, which, being put from thence, went and laid himself down betwixt her head and body, and being besmeared with her blood, was caused to be washed…”

On Walsingham’s orders, Mary’s head and body were then encased in lead and put inside a heavy coffin.

Although London rejoiced at the news of the execution, Elizabeth did not. When she was given the news at 9am the next day, “Her countenance changed, her words faltered, and with excessive sorrow she was in a manner astonished, insomuch as she gave herself over to grief, putting herself into mourning weeds and shedding abundance of tears”. So great was Elizabeth’s fury that Walsingham fled to his home, pretending to be ill and Leicester and Burghley were banished. Poor Davison, the scapegoat, was arrested, tried and sentenced to imprisonment in the Tower and heavily fined. Burghley managed to rescue the poor man from being hanged.

Elizabeth then had to deal with the aftermath of Mary’s execution which included the Pope calling for Philip of Spain to invade England as soon as possible and Henry III of France calling Elizabeth “this bastard and shameless harlot”, but by April things had calmed down and there seemed that there were to be no reprisals from Catholic Europe.

On 30th July 1587, Mary Queen of Scots was collected from Fotheringhay Castle and buried at Peterborough Cathedral with the royal honours deserving of a queen. In 1612, Mary’s son, King James I, ordered that his mother should be moved from Peterborough to Westminster Abbey and it is there that she can be found today, in a chapel opposite that of the woman who signed her death warrant, Elizabeth I.

Sources

- “Elizabeth, the Queen” by Alison Weir

- “Elizabeth’s Women” by Tracy Borman

Tis so interesting to read about My children great great great grandfather.

They have had a very interesting great grandfather William Davison who was the minister of aboriginal affairs at Port pirie ,S.A.,he was an Engineer arrived from England in the middle of the 1800,he avoided quarantine by swimming a shore with another English man who become THe high commissioner of South Australia .

Very interesting the Davison’s men.

I agree with Cynthia. Mary’s imprisonment was very harsh, she had come to seek help from her cousin Elizabeth, only to be kept a prisoner for 18 years. They were cousins, and yet they didn’t even meet face to face. Elizabeth didn’t want Mary on her throne, and till the Babington Plot, she didn’t have any proof of Mary’s plot. Dying at 44 years old, that was almost half of Mary’s life time. There isn’t any excuse to that. Love your website though, Claire! Royalty has always fascinated me.

Ann says:

September 27, 2011 at 12:54 pm

“Mary Queen of Scots was plotted against by Cecil and also the extreme Protestant John Knox (who wanted her dead from the outset) and used as a political pawn by the powerful Guise family in France. She did not wish to return to Scotland, preferring the continent but was cynically blocked from marrying Don Carlos of Spain by her mother in law Catherine de Medicis. She was a very kind and caring person and loved her French husband dearly so unlike the cunning and ruthless character of Queen Elizabeth 1st.”

I totally agree with you.

“MariAn O’Brien says:

August 15, 2012 at 9:27 pm

The ROCK: After signing the Death Warrant, Queen Elizabeth asked jail-warden Paulet to MURDER Queen Mary, indicating that Q/Eliza wanted Queen Mary dead just didn’t not want to be held responsible in history. The Death Warrant had first been ordered by Q/Eliza in 1569. long before the Walsingham plot, called Babington.

The conviction at Fotheringay was based on a forged letter written by Queen Elizabeth’s spy, Phellipe.

HARD PLACE: Q/Eliz ordered an English invasion Scotland in 1559/ 1560 and again in 1570. Then complained that Queen Mary (then of France) flew the quartered arms of England at Vosges in 1559. Meanwhile Queen Elizabeth signed many of her official documents as Queen of France. Scottish Rebel leader Moray had been receiving money as Q/Eliza’s employee since 1559. Q/Eliza gave him safe asylum after Moray led a treasonous rebellion in 1565 and safe asylum to the murderers of Rizzio. Q/Eliza’s spy was present the very day of Darnley’s murder and sketched in the Kerrs in the AM picture who had been there in the PM. How would Q/Eliza know to send a spy that knew about the details of the Darnley murder to be there that day? Q/Eliza promised Queen Mary aide while imprisoned by Moray at Lochleven then re-imprisoned when she sought passage to France.

How many times did Queen Mary invade England – None. How many times did Queen Mary interfere in English sovereignty while a sitting Queen – none.

The casket letters were a rumor by Moray for one plus half YEARS before he was able to actually produce them at York. The Letters that took Moray 16 months to forge are the only evidence against Queen Mary related to Darnley’s murder. And they were produced by a chief murder suspect who usurped the crown.

There is far more evidence that the Darnley murder was planned by Queen Elizabeth and Moray to be Queen Mary’s downfall through slander. And the 19 years imprisonment murder request by Q/Eliza is hard evidence of the same.”

This is fascinating and I believe every word of it.

“Serena says:

November 5, 2015 at 2:39 am

I agree with Cynthia. Mary’s imprisonment was very harsh, she had come to seek help from her cousin Elizabeth, only to be kept a prisoner for 18 years. They were cousins, and yet they didn’t even meet face to face. Elizabeth didn’t want Mary on her throne, and till the Babington Plot, she didn’t have any proof of Mary’s plot. Dying at 44 years old, that was almost half of Mary’s life time. There isn’t any excuse to that. Love your website though, Claire! Royalty has always fascinated me.”

I agree with this also.

Laura Guilfoyle says:

October 26, 2014 at 1:24 am

Queen Elizabeth was a coward who could not bring herself to sign the warrant for her cousin’s death and asked her jailers to murder her quietly instead. Everyone knew that her promises meant nothing. While Mary may have been reckless, she was never a coward and in the end of the day, it was her son who ruled England while Queen Elizabeth died barren! The present day English monarchy owe their claim to the throne from Mary, Queen of Scots, not Queen Elizabeth.

I agree with this also. Sadly it reminds me of what her father Henry Vlll did to her mother. They both played the innocent victim. Poor Anne, It was probably a good thing she wasn’t around to see how her daughter turned out.