Today is Good Friday and I thought I’d share with you how it is usually commemorated in my nearest town – preCovid!

In medieval and Tudor times, Good Friday was the day to prepare the church’s Easter Sepulchre, a stone or wooden niche, which represented the crucified Christ’s sealed tomb. This sepulchre was filled with the consecrated host and an image of Christ. It was then ‘sealed’, by covering it with a cloth, before candles were placed around it and lit. Just as the Roman soldiers guarded Christ’s tomb, members of the congregation would take it in turns guarding the sepulchre.

There would also be a special ceremony at church, known as ‘creeping to the cross’. the clergy would get down on their hands and knees, and ‘creep’ to the cross, to represent Christ’s suffering. Once they got to the crucifix, they would kiss the feet of Christ. Then, the crucifix would be taken down into the church for parishioners to do the same.

The Reformation changed things, with the creeping to the cross ceremony coming to an end in Edward VI’s reign. However, when the Catholic Mary I came to the throne, she revived the practice.

Another tradition associated with Good Friday was the blessing of cramp rings with holy water. These special rings would then be distributed to sufferers of epilepsy and cramps. Touching for the king’s evil was also often carried out. It was believed that monarchs had the divine gift of healing and that by touching or stroking the neck of someone with scrofula, a type of tuberculosis, they could heal the sufferer. The sufferer could also be given a touch-piece, a coin, such as an angel coin, that was blessed by the monarch and which could be pressed to their neck. Mary did this during her reign and although Elizabeth I abolished creeping to the cross and the blessing of cramp rings, Elizabeth did touch for scrofula on certain feast days. In her thesis “‘Would I Could Give You Help and Succour’: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Touch”, Carole Levin writes that Elizabeth’s keeping of such a practice led many Protestant in her reign to believe that she “had failed to truly purify the Church” but other Protestants explained that “Elizabeth’s touching as merely prayerful intervention to God, not a miraculous cure.”

Creeping to the cross is still carried out in some churches today.

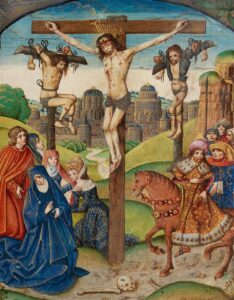

Here is an illumination of Christ’s crucifixion from the Vaux Passional, a late 15th/early 16th century manuscript, which is thought to have been prepared as a gift for King Henry VII.