A Response to the theory that Robert Dudley murdered his wife, Amy Dudley (nee Robsart) by Christine Hartweg

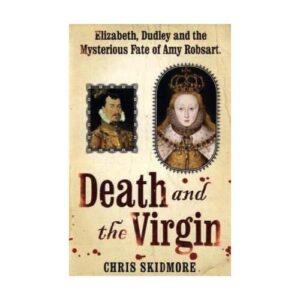

Thank you, Claire and Bess Chilver and all the others! I am horrified by Skidmore’s article! However, even in his book he is not keen at all to give other people their due. Citing manuscript sources, he sometimes has used secondary books in reality (I noticed this because he copied the errors or the direct assossiation).

Bess Chilver’s comment: “Skidmore is clearly of the view that Amy was murdered. He has looked for evidence to fit that theory. He has completely ignored the concept of “Cui bono?”” IS THE NAIL ON THE HEAD! But Skidmore is successful and so he can mislead countless innocent readers. He has no evidence to accuse anyone, but it is a PR catastrophe for Robert Dudley. It’s such a pity!

Please read also my amazon.co.uk review

“Concocted evidence”,

By Christine Arabella (that’s me, really) at http://www.amazon.co.uk/product-reviews/0297846507/ref=dp_top_cm_cr_acr_txt?ie=UTF8&showViewpoints=1

STAIRS

The sketch of the stairs is from the late 18th century. Skidmore himself says the house was altered during the 1570s and later. In the chapter on Cumnor Place Skidmore mentions another stair leading directly to Amy’s chamber on the first floor (it was by far the best in the whole house, a separate, “spacious and elegant” appartment). There are apparently no surviving details about what kind of a stair this was, but it led from a groundlevel entrance from outside the courtyard to her room. The stair of the sketch, on the other hand, had an entrance from outside on the level of a landing and was leading to the gallery in the upper floor (this aisle of the house was quite distant from Amy’s chamber).

Later in the book Skidmore flatly says this stair was the one Amy fell down. It’s of course likely as it corresponds with the “pair of stairs” mentioned in contemporary sources, including Blount’s letter (which is very important), and apparently the villagers had a tradition that this was the stair in question. But what makes me furious is that he never mentions the other stair again. There is one detail in the coroner’s report which he does not comment upon, although in other cases he takes the report absolutely verbatim: it says that “being alone in a certain chamber (camera) … and intending to descend the aforesaid chamber by way of certain steps (gradus; ‘in English called ’steyres”) … there and then accidentallly fell precipitously down the aforesaid steps to the very bottom of the same steps”. They mention no gallery but a chamber in which she was alone (this could clearly be her personal appartment), neither do they mention a “pair of stairs” but only “steyres”.

Also, the stair in of the 18th century sketch into the gallery is quadrangular but was described as a circular newel staircase in a book about the same time! Skidmore uses both documents repeatedly but he ignores this oddity. But remember there was also the stair to Mylady’s Chamber!

ACCIDENT

The 5 mm wound is not so serious, although if the Galea aponeurotica at the bottom of the sculp is cut through, gaping wounds are the consequence, making a dramatical appearance. As for measuring the deepness of wounds this poses a major problem. According to the first-rate clinical/anatomical handbooks I consulted, this is practically impossible from the outside with cranial injuries. Let alone by putting your thumb into the wound (as Skidmore says without giving any source for this)! I really am not convinced how they were doing this: in case they forcibly thrust their thumb into the wound (as they must have done if that was the method) they would automatically have compressed the underlaying tissue, so I am not at all convinced that this tells us much!

Then there is the problem of what is a “thumb”; they used to measure things in “fingers” in Tudor times, meaning parallel fingers on your hand; but you can never put parallel thumbs (or fingers) into a wound this way! So what is meant? They probably used some kind of measuring stick, but it seems fundamentally problematic to “measure” the “deepness” of such injuries. Skidmore neither explains why a thumb should be as much as an inch (my two thumbs do come to about 3.8 cm). I wonder if he measured his great toes instead.

The report does not specify the location of the wounds. It’s interesting that in case the deep one was around the lower temple (on the side of the skull, just before/beside the upper half of the ear) it would point to a basilar skull fracture, a typical injury in (stair) falls; but also in suicides, when people jump from on high, even into a canal or river from the wharf, for example. That’s interesting in the light of Bess Chilver’s comment on Tudor stairs height and a possible suicide!

Skidmore hints in his preface that he consulted two medical experts for Amy’s wounds but never mentions them or other forensic experts in the book proper. He gives statistical material from stair acccident research clearly stating that even such injuries as Amy’s are entirely compatible with a fall from the stairs (even short stairs; they seem to be statistically more lethal than others). That there were (apparently) no other wounds on her body or limbs is no problem either, although Skidmore does not go into the problematic matter of the visibility, later discernability, of hematomas on a dead body after a lethal accident. The mere silence of the experts he consulted tells me that they couldn’t tell him that an accident was out of the question, or even unlikely.

SUICIDE

He explains this away with Amy’s religiosity and the punishments which were due for committing suicide; the problem is that according to this logic there wouldn’t have been suicides at all in early modern England.

ILLNESS

Skidmore is very keen to dismiss the possibility that Amy was ill; he is scathing to historians who relied on the April 1559 de Feria quote that she had “a malady in one her breasts”. The original at the Archivo General de Simancas, according to Dr. Simon Adams (Adams, Simon (ed.): “Household Accounts and Disbursement Books of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester” Cambridge UP, 1995, p. 63), says: “está muy mala de un pecho” (“she is very ill in one of her breasts”). The odd, and in my view significant, thing now is that Skidmore gives another version without any source (p. 227), he just cites the English CSPSpan (1892), which has no Spanish version: “enferma y mala de un pecho” (which comes to about “ill and sick in one of her breasts”). Now, he has probably a reason for this kind of deception; believe me, I stumbled upon several tricks of this kind, very difficult to detect for most readers, which makes me furious and sad!

Another reason why Skidmore thinks Amy was not ill at all was that she ordered dresses and the like before her death; I know from personal experience that’s ridiculous: of course you continue shopping when you know you’re dying! (Amy wanted her dress as soon as possible). Skidmore mentions in passing (p. 260) that Sir Thomas Parry supported a Dudley marriage of the Queen — before Amy’s death that is, so was he of the opinion that she would die soon? He became “half ashamed of his doing for the Lord Robert” after Amy’s scandalous death. This could point to an illness – pace Skidmore.

POISON

He imagines Amy stalked by Dudley’s evil followers for 18 months before her death! They try to poison her: The sources are only about 5 for this: The “Journal” (“Religion, Politics, and Society in Sixteenth-Century England”, Camden Fifth Series, Cambridge UP, 2008) says that she felt herself poisoned in the spring or so of 1559 at Mr. Hyde’s house where she then lived; Dudley found her another lodging because of this (Journal p. 66). The Imperial ambassador Brüner and de Quadra report in November 1559 (Brüner again in January 1560) that Lord Robert sent his wife poison, and they have it from a very good source or so. Now these two ambassadors shared lodgings and seem to have repeated to each other their own stories. Especially Brüner hated Dudley extremely, yearning for his execution(!) or at least asassination: “that he will follow in the footsteps of his [forefathers] … that he will one day meet with the reward he so richly deserves.” This was almost a year before Amy’s death – the ambassador was blaming Dudley for Elizabeth still not having married the Archduke Charles!

Skidmore backs this up with the story of Dr. Baily from “Leicester’s Commonwealth”, the virulent propaganda book against Leicester of 1584! Because Baily, in 1584, apparently didn’t officially protest against what was said there about him, Skidmore seriously thinks he can use this as evidence that Dudley’s henchmen tried to use the doctor (in vain!) to poison Amy! He is also self-contradictory in that in this case he states that Amy was ill! (Baily became very famous and from at least 1570 Leicester’s trusted personal physician; decades later treated the Queen for toothache).

In the end Skidmore even cites Cecil’s notorious remarks to de Quadra that “they” (tradtionally Robert and Elizabeth) would give out Amy was ill only to poison her, as a proof that she was. Now, he stresses that Cecil said this after he knew she was dead to capitalize on the event, but he nevertheless thinks he can use it as evidence that Dudley’s people were poisoning her!

As regards the “Journal” one has to see that the whole page about Amy was only written after her death, so everything was said in hindsight. The “Journal” is extremely anti-Dudley (see commentary in above edition), and its author says he never saw Robert until after Amy’s death. One also has to account for the age: there was a general hysteria; everybody felt themselves constantly poisoned, and yet archeologists and serious historians have found no evidence for these claims — see Borgia, Catherine de Medici, the Florentine Medici etc. Alternatively, it’s entirely possible that the poison charges, which come all from sources hostile to Dudley, mirror some real ailment of Amy’s. It’s interesting that the “Journal” says in hindsight that Dudley’s men spread she was dead long before she was (a cornerstone of Skidmore’s theory, this).

VERNEY

The “murder evidence” rests largely on this dialogue:

“Howbeit it was thought she was slain, for Sir —- Varney was there that day and whylest the dead was doing was going over the fair and tarried there for his man, who at length came, and he said, thou knave, why tarriest thou? He answered, should I come before I had done? Hast thou done? quoth Varney. Yeah, quoth the man, I have made it sure.”

This is also from the c. 1562 “Journal”. Skidmore backs this up with a few picks (only those that suit his purpose) from the notorious propaganda book “Leycester’s Commonwealth” of 1584. As has been pointed out by scholars years ago, this proves nothing but that there was a tradition of gossip involving Varney. — As is clear even from the above chronicle, it was by no means inside information but common talk. Skidmore is unwilling to distinguish between possible origins of gossip and a proof for murder and ignores incongruities in his sources (also in other cases).

Varney’s murder motive, loyalty to his master, is not at all convincing. Skidmore argues Cecil would not have risked his position by murdering Amy. Sure! But neither would have Dudley! He would not have risked the axe for murder after having narrowly escaped it for treason (he had also lost 55% of his immediate family between 1553 and 1557 alone; so his ambition was probably balanced by his desire to live). It was natural that all suspicion would fall on Dudley (the more so if the crime occurred in his wife’s lodgings!), as people were immersed in an incredible amount of slanderous gossip regarding him and the Queen. That was a thing his servants, as his enemies in high places, were well aware of.

MR SMITH / LETTER / JURY

The “evidence” for Dudley’s interference with the jury is that the jury’s foreman Sir Richard Smith, formerly “the Queen’s man” and later mayor of Abingdon (the place where Cumnor is located), received some stuffs to make clothes of from Robert Dudley in 1566 — six years after the event. Skidmore does not discuss why the “Mr. Smith, the Queen’s man” of 1566 should be the same Smith as the foreman. This is in fact unlikely, as Sir Richard Smith was mayor already in 1564/1565, so he wouldn’t have been any longer a mere “Queen’s man” by 1566. Neither would he have been “Mr. Smith” but more likely “Sir Richard Smith”. In the scholarly edition of Leicester’s household accounts by Dr. Simon Adams there figure ten Smithes alone in the index: two men are called Ralph Smith, one of them another “Queen’s man”. And even if it was Richard Smith of the jury, that doesn’t prove why Dudley should have known him before the death of his wife, nor does it prove anything else.

The same goes for John Stevenson, another jury member; Skidmore, not bothering to explain why, thinks he was the same man as John Steaphinson Ferrar from a 1559/1560 wages list of Dudley’s. The Stevenson of the jury had a brother Edward (also in the jury), while the Stevenson of Dudley’s list had a son Robert listed as groom of the stable near his father. I would personally think they were of a bit lower social level than the jury members. The author also tries to implicate Dudley via some payments he made at the end of 1560. Other than Skidmore tries to convey, there was nothing ominous about these: Francis Barthewe, whom Skidmore sees as a mysterious “stranger”, was a Flemish merchant to whom Dudley had owed money for some five years (comp. p. 40 of the Accounts). Anthony Butler MP was repaid a “bond” — a normal procedure. For allegedly suspicious payments to Anthony Forster see my February comments at https://www.elizabethfiles.com/did-robert-dudley-murder-amy-robsart/3611/

Dudley wrote to his agent Thomas Blout:

“I have received a letter from one Smith, one that seemeth to be the foreman of the jury. I perceive by his letters that he and the rest have and do travail very diligently and circumspectly for the trial of the matter which they have charge of, and for anything that he or they by any search or examination can make in the world hitherto, it doth plainly appear, he saith, a very misfortune; which, for mine own part, Cousin Blount, doth much satisfy and quiet me.”

Of course Skidmore reads all kind of sinister meanings into this. Dudley goes on to say that he doesn’t know Smith nor any of the jury and that he is right glad thereof or so. Please see here for the complete correspondence (five letters) between Dudley and Blount. Apart from the Coroner’s report this is the only first hand, “real”, evidence about Amy’s death: http://www.archive.org/details/amyerobsartearlo00adlauoft from p. 32.

Typically for his working style, Skidmore interprets the first response from Blount to Dudley half-fictionally, distorting basic facts; he also flatly implies that Dudley and Blount must have been sorry that “most” of the jury had already assembled (before Blount could pick them), when there is every evidence that Blount was happy about this; and it was clearly the whole jury: Blount’s original “Before my coming the jury were chosen” contains no “most” and there is none anywhere near!

The 15 jury members’ verdict on oath was accident, “as they are able to agree at present”. Skidmore makes a lot out of this disclaimer (by its very frankness it does not smack of intervention by evil forces to me).

DUDLEY’S NEGLECT / HYPOCRISY

It is always said on the basis of the household accounts that Dudley had not seen Amy for over a year; while entirely probable, it is not absolutely sure (Adams Household Accounts p. 383), and contradicted by the “Journal” (p. 66). He certainly wanted to visit her for months when she died. He sent her presents and she was rather independent, also financially (Adams again).

“And her death he mourneth, leaveth the court … Himself all his friends, many of the Lords … and his family be all in black, and weap dolorously, great hypocrisy used.” (“Journal”).

Skidmore cites this as coming from an eyewitness when it comes from the “Journal”, whose author didn’t recognize Robert, an extremely well-known figure at court.

Comment from Claire

Thanks so much, Christine, for taking the time to write this response to Chris Skidmore’s book. I haven’t read his book yet, but from the articles I’ve read, and from your brilliant assessment of the evidence and his theory, I don’t see there being any reason to suspect Dudley of being involved in Amy’s death. I hate the way that historical characters get maligned in this manner, poor Robert Dudley. While I don’t like the way that he neglected Amy and the emotional hurt he caused her, Dudley was not a murderer. Innocent until proven guilty, and there’s just no proof.

Thanks so much, everyone, for all the wonderful comments on the previous posts on this subject.

There’s a great video on Amy Robsart and Robert Dudley at littlemisssunnydale’s YouTube channel at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qtkH0EfGCCM